Leading Roles

Students take on dramatic roles to put theory into practice

Regis Today Fall 2016

BY KRISTEN WALSH

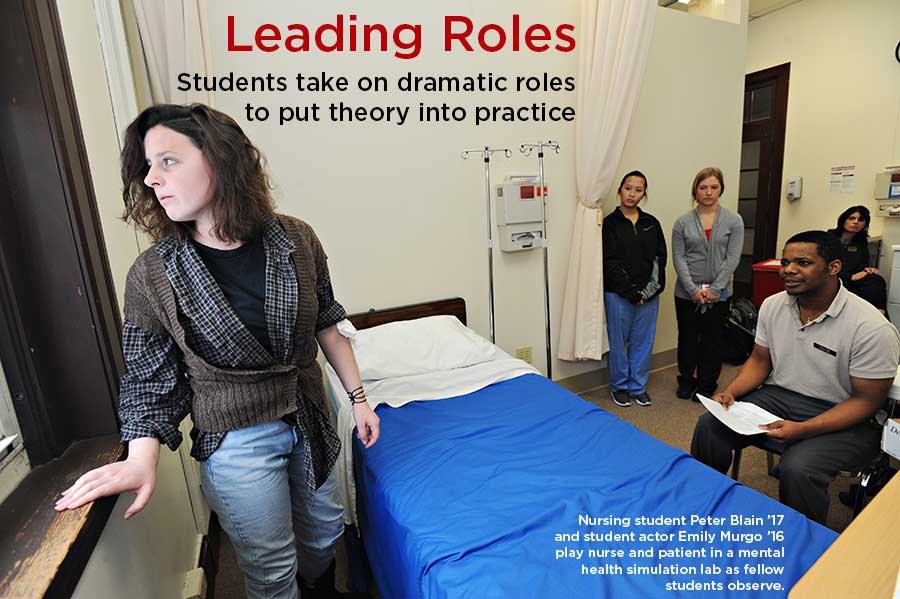

A nurse conducts a risk assessment on a patient suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder to determine the threat for self-harm or harm to others on a psychiatric hospital unit. Another patient has a bipolar, manic episode. These simulated scenarios mimic a day in the life of nurses and psychiatric patients; only this time the patients are played by Regis acting students, and Regis baccalaureate nursing students work diligently to provide care.

The interdisciplinary production is the masterpiece of Associate Professor of Nursing Denise Soccio, DNP, who developed three mental health simulation labs as part of her doctoral thesis (successfully defended on August 11, 2016, to complete her Doctor of Nursing Practice degree). Soccio collaborated with Associate Professor of Theatre Frans Rijnbout, PhD, to bring 50 nursing students and four acting students together for the project.

“I originally considered using virtual patients, but in addition to obstacles like high cost and computer glitches, I knew that it would take away from the reality,” Soccio says. “And if a simulation doesn’t feel real, nursing students won’t take it seriously and it won’t be educational.”

With that in mind, she reached out to Rijnbout to recruit Regis acting students experienced in improvisation.

“Although the actors would have case studies and scripts, they needed to have solid improvisational skills to react to a nurse during the scenario in order to drive particular themes,” Rijnbout explains.

Soccio put on her director’s hat to prepare student actors to take on the emotional turmoil and angst of mental health patients. One suffered from depression and had hidden a blade in the hospital bed to use for wrist-cutting. Another who was diagnosed with psychosis heard voices (student nurses heard pre-recorded audio with headphones) and threatened safety on the unit.

Nursing students put themselves in the shoes of a psychotic patient by "hearing voices" on pre-recorded audio.

Nursing students put themselves in the shoes of a psychotic patient by "hearing voices" on pre-recorded audio.“One of the great things about incorporating live actors into the simulation labs is that we can show the nursing students that there’s more to a patient than just a diagnosis,” says student actor Emily Murgo ’16. “The patient could present with anything from a self-inflicted laceration of the wrist to a grandiose delusion that she’s a Broadway star, or even be triggered into a post-traumatic stress disorder flashback. For me, it was important for the students to see these behaviors, but also for them to realize that the patient is vulnerable and relies on them for care and support.”

Nursing students were provided patient demographics and background, reason for admission, and three learning objectives before taking on roles as primary nurse, charge nurse, and medication nurse. During the lab, they conducted patient interviews and risk assessments and determined therapeutic responses to agitated patients while being observed by peers on communication, safety, and delegation. A debriefing session followed.

“In addition to faculty feedback, actors presented the patient perspective during debriefing,” Soccio says. “This is where a lot of learning took place.”

“�Nurses have certain medical protocols to follow, but a patient’s actions - physical and emotional - don’t come straight from a textbook.”

Nursing major Peter Blain ’17 found it interesting to collaborate with students to learn about diverse cultural beliefs on mental conditions. “We all have different beliefs about what causes someone to become psychotic, but we’re educated to know and appreciate nursing interventions to help patients and others remain safe. The ability to hear about cultural similarities and differences was a very enriching part of the lab.”

Finding Common Ground

Though acting and nursing are very distinct disciplines, they do share certain commonalities—including improvisation.

“An important part of acting is being able to jump into unexpected situations,” Rijnbout says. “You or a fellow actor may forget lines or change something, and it’s critical to stay on your toes in order to react and keep the show moving.”

The same, Soccio says, happens in the field of nursing. “Nurses have certain medical protocols to follow, but a patient’s actions—physical and emotional—don’t come straight from a textbook. People have individual characteristics and you have to be ready for the unexpected.”

Empathy is another attribute shared by both actors and nurses.

“Acting is strongly based on empathy with the character, as you have to put yourself in their shoes,” Rijnbout explains. “Student actors researched the background of the patients: where they come from, what they fear, and what it’s like to live with a mental illness.”

The British Journal of General Practice reported that empathy is linked to lowering patients’ anxiety and distress, and delivering significantly better clinical outcomes (Stewart W. Mercer and William J. Reynolds, 2002). Not surprisingly, patient-centered care is on the rise in the field of healthcare. According to the Institute of Medicine, it is defined as “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.” Empathy plays a key role.

“Although simulation is a concept that was initially developed for hands-on nursing care, studies show that students can also learn effective communication skills,” Soccio notes. “This ties in to learning how to be empathetic toward patients.”

Preparing for Life's Role

Market demand for nurses is on the rise, with a projected need for 1.05 million nurses by 2022, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But a 2014 study by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing reported that U.S. nursing schools turned away 78,089 qualified students from baccalaureate and graduate nursing programs in 2013 due to an insufficient number of faculty, clinical sites, classrooms, clinical preceptors, and budget constraints.

“There’s difficulty to secure appropriate mental health inpatient clinical placements for pre-licensure students because there are multiple schools competing for limited sites,” Soccio notes. “If students don’t have appropriate clinical opportunities to learn effective communication, assessment, intervention, and critical thinking skills, patients with mental health disorders won’t receive high quality, competent care.”

Inspiration for Soccio’s project came from The National Council of State Boards of Nursing National Simulation Study, which provides evidence that simulation can effectively replace traditional clinical hours up to 50 percent (Hayden et al., 2014). She revised three existing case scenarios and scripts from the University of Maryland and developed two additional ones based on research. The setting: simulated labs—with hospital beds, computers on wheels, and medical equipment—in Regis’ Clinical Resource and Simulation Center in College Hall.

Nursing students report that the simulation helped them prepare for clinicals.

“The scenarios made it a lot easier to learn how to intervene and react depending on the disorder,” Blain says. “My top takeaways included patient safety as a number one priority, and the impact that a nurse’s actions can have on helping or hindering a patient’s success.”

The spring program was so successful that Regis has used the model as a best practice for other core nursing classes at Regis—including for 16 part-time nursing students during the summer and for the pediatric/maternity program.

“Life is a continuous improvisation, and the simulations mimicked real-life situations,” Rijnbout says. “We all play roles: the role of patient, nurse, teacher, wife, and father, for example. We’re always experiencing new situations.”

Soccio agrees. “As much as you prepare for nursing, it’s the experience that provides the confidence to succeed. Using a non-threatening environment helped to boost students’ knowledge of mental health, self-confidence, critical thinking, and decision-making skills. This can all be taken to the bedside.”

SIMULATION HUB

The Clinical Resource and Simulation Center at Regis is a hub of activity for all pre-licensure nursing students. The center, run by lab faculty trained as certified simulation healthcare educators, houses four simulation labs and multiple debriefing rooms.

Among the programming: a “clinical boot camp” simulation for beginning nursing students and a multi-patient simulation and focus on prioritization and delegation for graduating students. Simulation scenarios in maternity include a postpartum hemorrhage and a newborn assessment utilizing low-fidelity newborn manikins.

“These areas are often lacking in novice nurses as they transition into professional practice,” says center Director and Associate Professor of Nursing Patricia McCauley, DNP. “Regis is preparing future nurses with evidence-based best practices in simulation.”

Read more articles

Read the entire magazine online

Read the entire magazine in PDF format