The first time Ashley “Lee” Campbell ’17 and Regis graduate students Amanda-Elyse Cutter and Bradford “Brad” Moore met Nancy Schön, they were—in the words of their professor—“politely intimidated.”

Rightfully so. Schön (pronounced “Shern,” a name with more Hungarian than German roots, she says) is a world-renowned sculptor, born in Boston and raised in Newton, Massachusetts. Her public art covers the globe from Boothbay Harbor, Maine, to Tel Aviv, Israel. Families flock to her iconic bronze sculptures of Mrs. Mallard and her ducklings in the Boston Public Garden, a tribute to the beloved children’s book “Make Way for Ducklings.” (There’s a Mallard family in Moscow, too.) Campbell and Cutter remember playing on the Boston ducklings as children.

Who knew that a graduate college course would lead them to the very artist who helped cultivate their childhood memories?

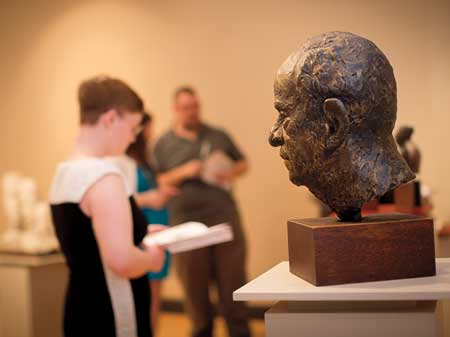

The unlikely trio—Campbell, 21, Cutter, 22, and Moore, 41—had one assignment for their graduate Museum Studies Practicum with professor Kathryn “Kate” Edney, PhD: to curate a themed exhibit for the university’s Carney Gallery in the Fine Arts Center.

An exhibit is not unlike a live performance. There’s the behind-the-scenes process, then the curtain goes up. No turning back.

Past practicum exhibits drew on artifacts and archives; here was a living, prolific, famous artist with whom the students had to work.

“None of us knew what this [was] going to be,” admits Schön. “They didn’t know what to do with me, I’m sure.”

Schön, 88, had never done anything like this before, either—essentially letting strangers into her home to select pieces to show and then decide, for the exhibit, what goes where. She had an exhibit at Regis in 1977. But this was entirely different.

“‘Oh my God, what am I going to do with this group?’” she recalls thinking. “I had no idea what I was supposed to be doing.”

The only certainty was the exhibit’s theme, “metamorphosis,” and the looming deadline to pull it together for a 2017 spring semester opening.

“[Nancy] took a leap of faith working with the students,” says Edney, who, along with teaching the practicum, is the graduate program director for Heritage Studies, an assistant professor in the Department of Humanities, and associate dean of academic assessment at Regis.

Schön calls the experience an adventure. “That’s part of the excitement of life,” she says. “Not knowing what’s coming up.” This September Schön will publish her first book about her work and public art.

The students wanted the exhibit to look professional, not like it was put on by, well, college students. Ultimately, they wanted Schön to be happy.

The students wanted the exhibit to look professional, not like it was put on by, well, college students. Ultimately, they wanted Schön to be happy.

An exhibit is not unlike a live performance. There’s the behind-the-scenes process, then the curtain goes up. No turning back. That’s what happened at the opening reception February 16. All gathered awaited the artist’s remarks.

“I am thrilled,” Schön told the crowd. “This is just a delight and the best show I have ever, ever had.”

The students, humbled and excited, were also exhausted and happy. “We did Regis and Nancy proud,” says Moore, admitting: “I won’t really be relieved until all these things are safely back in Nancy’s house.”

“Metamorphosis: The Art of Nancy Schön” contains 36 pieces, sculptures cast in various mediums, that span Schön’s life in ways no exhibit of hers has to date. There are personal pieces that have never been shown, pieces from her high school days, and “Butterfly” (2017 bronze) suspended in air, cast for the exhibit.

Anita Diamant, renowned novelist and Schön’s friend, came to the opening. “I hadn’t seen the unfinished pieces, the rough drafts,” she said. “Her experiments, they’re fantastic.”

Campbell’s mother, Kim Campbell—a registered nurse and a graduate student in Regis’ nursing program—saw the exhibit not only to support her daughter but because she says such an exhibit is a “critical” complement to the sciences.

“This kind of thing opens you up to the depth and breadth of human experiences,” she says. “So I’m glad it’s a priority at Regis. The deeper our understanding of the human condition, the better we’re able to connect to one another.”

A Treasure Hunt

When the students walked into Schön’s imposing Victorian house last September, they were excited and nervous. Her sculptures were everywhere. “I remember being very worried about how delicate the artwork might be,” says Campbell.

Schön’s hospitality broke the ice. She fed her new acquaintances sushi and asked them questions about themselves to get to know them. “She seemed very down-to-earth,” recalls Moore, who wasn’t sure what to expect from a high-profile artist. “She was just so easy to talk to from the get-go.”

Soon the talk turned to the exhibit. Schön led the students on a grand tour of her home and studio, pointing out pieces—a bust of her father, a horse’s head—that she liked.

Soon the talk turned to the exhibit. Schön led the students on a grand tour of her home and studio, pointing out pieces—a bust of her father, a horse’s head—that she liked.

“At first I thought I would have a normal show of all my work I’ve had a billion times,” Schön says. Then one night in bed, the theme metamorphosis played over in her mind. “I thought, ‘You know, I have a lot of stuff here in my cellar and attic’—I didn’t even know [what I had]. So I got up the next morning, started looking. This is a much more interesting thing.’”

Her epiphany gave the students direction.

“There were lots of surprises,” says Schön. “It was sort of like a treasure hunt.”

With each trip to Schön’s house (there were about four), the students deliberated back and forth about what to include and why.

“She definitely was not forcing any piece on us,” says Cutter. “We picked out pieces that Nancy wouldn’t necessarily pick out.”

One of those was “Balancing Boy” (1974 bronze)—a small figure of a boy catching his balance with outstretched arms. The right hand is missing.

“She didn’t think anyone would want to see it because it was damaged,” says Cutter. But the students liked it because it shows Schön, a mother and grandmother, as a proud mom because the statue is modeled after her son when he was a young gymnast.

Edney arranged for professional art movers to bring the pieces to the gallery. Cutter, Campbell, and Moore deliberated again over placement. “We had to talk a lot of things out,” says Campbell. At one point Schön expressed dislike for a couple of pairings; the students conferred and made changes to the exhibit. “It wasn’t tense,” says Campbell. “It was the opposite.”

Eventually they grouped like objects together: the interpretive or metaphoric pieces at the beginning; people, including busts and figures, next; then the animals. “Raccoon” (1995 bronze) is the one piece you’re allowed to touch, a hallmark of Schön’s public art.

Two pieces done in 1971—“Hands” (bronze) and “Crying Mask” (painted bronze)—mark “a dark period” in her life. “It was hard,” she says of that time. “We didn’t have a lot of money. We had four kids, and we were moving all over the place.”

“[the show is about] the younger me and the transformation to the older me. I was sort of surprised [by the] show—it gave me a perspective of myself.”

NANCY SCHÖN

If a piece didn’t make the cut, it was likely too delicate.

“She definitely uses her art in almost a social-activist way,” says Moore.

Schön says the show is about “the younger me and the transformation to the older me. I was sort of surprised [by the] show—it gave me a perspective of myself.”

Schön says the show is about “the younger me and the transformation to the older me. I was sort of surprised [by the] show—it gave me a perspective of myself.”

The students saw that. Moore points to “Mephistopheles” (1957), a pitchfork-and-chain welded metal piece. “She made that while in a camp in Maine,” he says. “It’s such a departure from everything we see from her.” She used pieces from a junk pile and welded them together with a blowtorch. “That piece speaks to me,” Moore says.

For the students, the show was about coming together over hundreds of decisions—what color should the pedestals be? How far apart should the sculptures stand?

Even Kyle Kahl ’20, who produced the catalog, was making changes to the layout at 3 a.m. before the printing deadline. (Moore’s wife, Maura, a professional photographer, photographed the art.)

“I think group work was a big part of the development,” says Campbell, acknowledging that other courses involve group work. “This was a six-month, high-stakes kind of thing, so it’s very different. We learned to work well as a team.”

Before the opening reception, Cutter, Campbell, Moore, and Edney take a breather with Schön. She compliments the young women, decked out in dresses and heels. “Don’t you look gorgeous, you two.” Turning to Moore, she adds: “And handsome! Did you shave?” she teases.

Schön shows off the miniature gold pendant around her neck she made on a 3D printer. “My exact Mrs. Mallard,” she says. “She’s got diamonds in her eyes!”

The triumph of the evening gives everyone pause; rest, finally, and a moment to reflect.

“I think we are friends,” says Schön of her young producers. “I hope!” She smiles, looking to Edney then to Cutter, Campbell, and Moore, a Mrs. Mallard doting on her ducklings. “I love them—they’re just wonderful young people.”

“Metamorphosis: The Art of Nancy Schön” ran from February 16 through May 9 at the Regis Fine Arts Center Carney Gallery.

Read more articles

Read the entire magazine online

Read the entire magazine in PDF format